Film Club

The first Saturday of each month at Coledale Community Hall at 7:30pm. Tickets here

COMING UP

Film Club is curated and hosted by film expert Graham Thorburn, and is open to anybody interested in seeing, thinking, and having fun talking about films.

Each Film Club night starts with some background information – the times and context of the film’s making, the people who made it, and something notable about the content or techniques of the film – perhaps even a bit of gossip. After the film screening, the film is discussed over a cup of tea and a biscuit, or a glass of wine (BYO). You can read some of Graham’s introductions to previously screened films below.

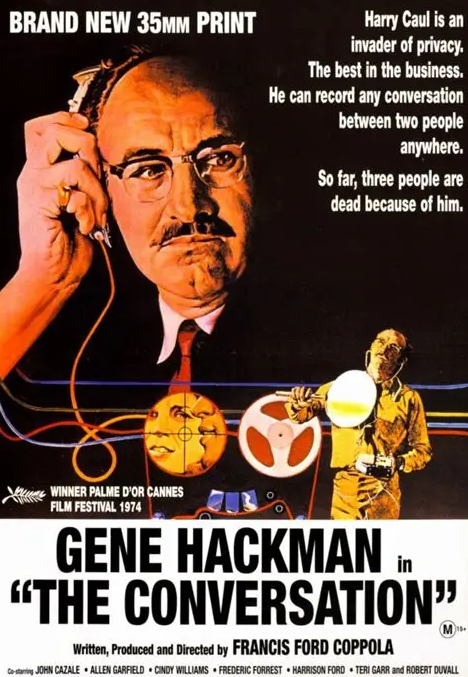

August 2025 - The Conversation

Have you ever had that experience of having a conversation near your phone about, say, travelling in Scotland – and then every time you open a browser for the next few weeks, your feed is filled with ads for travel in Scotland?

Well then, even though Francis Ford Coppola’s film The Conversation was written in the early 1970’s, it will resonate with you.

Coppola was having a very good run in the early 1970s.

The Godfather, released in 1972, was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, and won three: Best Picture, Best Actor (Marlon Brando) and Best Screenplay (Coppola and Mario Puzo – who wrote the book on which it was based).

Two years later he had two films in contention: The Godfather Part Two and The Conversation. Between them they were nominated for 14 Oscars, and won 6 (all to The Godfather). Amazingly, both films were nominated for Best Picture – though it is not as rare as it might seem. Nine other directors have achieved the same, though largely in the early days when studio directors regularly made 2 or more films a year.

10 directors with two ‘Best Picture’ nominees in one year:

Ernst Lubitsch (One Hour with You and The Smiling Lieutenant)

Victor Fleming (Captain Courageous and The Good Earth)

Michael Curtiz (The Adventures of Robin Hood and Four Daughters)

Victor Fleming (The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind)

Alfred Hitchcock (Foreign Correspondent and Rebecca)

John Ford (The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home)

Sam Wood (Kings Row and The Pride of the Yankees)

Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather Part II and The Conversation)

Steven Soderbergh (Erin Brockovich and Traffic)

But Coppola was the only one to also be the Producer of his films, because Coppola had parlayed his successes with the first Godfather film to give himself total creative freedom – Paramount funded his pictures but had no real control.

This really pissed off the studios and was to become a negative factor in Coppola’s career – for example, this created so much resentment at Paramount that they didn’t even place an ad in Variety announcing the release of The Conversation.

But, while Coppola was having a great run, the body politic of America was having a terrible run. A run that might sound strangely familiar these days.

In the early 70’s America was still heavily embroiled in the Vietnam war, and it was dividing the nation on cultural and generational lines. As well, there was a growing backlash against the changes bought by Lyndon Johnson’s administration – mostly the various Civil Rights Acts finally overturning Jim Crow in the Southern States, but also reviving the Equal Rights Amendment which, although finally passed by the Senate in 1972 under Nixon, still hasn’t been ratified by the required number of states to this day.

In the late 60’s the Republicans realised that many Dixiecrats felt betrayed by Lyndon Johnson. LBJ was a Texas Democrat, and the Dixiecrats thought that, when Kennedy was assassinated, they finally had their man in the White House, and he would put a stop to all this nonsense about equal rights and treatment for black people.

But Johnson was considerably less racist than Kennedy, and with a majority in both houses, instead of keeping the black man in his place (they would have used a much nastier word), he pushed through legislation to give African-Americans much more political and economic power, and backed the legislation up with federal action.

The Republicans, sensing an opportunity, successfully launched their ‘southern strategy’ to persuade all these former Democrat voters to vote Republican – a change that is still at the heart of the MAGA movement.

Ironically, the party of Lincoln became the party of racism.

The growing gulf between northern liberals and southern conservatives was perfectly captured by the 1972 presidential election, which pitted the incumbent Nixon against the Liberals’ darling, McGovern.

McGovern got smashed – winning only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia – but not before the famously paranoid Nixon had launched what became known as the Watergate burglary in an effort to ensure his own re-election.

Two minor (at the time) reporters at the Washington Post stumbled across the story, and pursued it relentlessly. But for two years their reportage barely registered. The Republicans successfully buried the story for nearly two years with a very successful ‘fake news’ campaign against the ‘liberal Mainstream Media’ (sound familiar?).

All that meant that what passed for the left in America in the late 60’s and early 70’s became increasingly distrustful of government – of what would these days be called the deep state.

In Hollywood this distrust was reflected in a new genre of movie – the paranoid thriller. To name just a few made in the early 70s: Klute, The Parallax View, All the Presidents Men, Three Days of the Condor and Marathon Man.

Ironically, although The Conversation appears to have very close parallels to the Watergate break-in, it was in fact written a few years before – and rather than Watergate, was inspired by Michael Antonioni’s film 1966 film Blow-Up.

It is, in effect, a remake of Blow-Up, with sound substituting for image as the source of narrative and moral ambiguity.

The other major difference between Blow-Up and The Conversation lies in the writing and casting of the central character. In Blow-Up we have David Hemmings – handsome, confident, unconcernedly amoral, and very groovy.

In The Conversation we have Henry Caul, Catholic, fearful and guilty, morally conflicted, and a Schlumpf, to use the technical term.

Which brings us to Gene Hackman, who died very recently, and who is the reason I chose this film. Because in my mind Henry Caul is one of Hackman’s two greatest performances, alongside ‘Little’ Bill Daggett in Unforgiven.

After serving in the Marine Corps in the aftermath of World War II, Hackman tried a few different career tacks before stumbling into acting classes at the Pasadena Playhouse in California in 1956, where, according to Hackman, he and his friend Dustin Hoffman were voted by the class the ‘least likely to succeed.’

I suspect Hackman invented this story, because all through his career Hackman was driven by resentment about being undervalued – so much so that, even when he was enormously successful (and he appeared in over 100 films) he had a reputation for turning somebody in the cast or crew into his enemy, so he could motivate his performance by proving they were wrong.

But for a decade it seemed they were right. Hackman managed to score a wide range of small supporting roles, but his most consistent role was as a waiter at Howard Johnson’s.

And then, in 1967, Arthur Penn cast him in a supporting role as the brother of Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty), which got him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor – and seem to define the sort of role he was right for – tough, hot-headed, not very bright.

And then, just to underline that, in 1971 he won the Best Actor Oscar for his role as Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle in William Friedkin’s big hit The French Connection.

But Coppola turned this casting on its head, and got from Hackman what I consider one of his two best on-screen performances (the other is in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven).

There is a trope in filmmaking called ‘casting against type’, and casting Hackman as Henry Caul is a great example of this.

Just imagine, for example, if Coppola had cast Hackman’s acting school friend Dustin Hoffman as Henry. It’s much more obvious casting – but for me it wouldn’t have been nearly as interesting because of its obviousness.

BTW, the word “Caul” has two meanings, which are both relevant to the character: It is a spider’s web, especially one that has insects trapped and wrapped up on it; and it’s also a semi-transparent membrane of skin that encloses some foetuses.

Irish superstition has it that, if a caul is found over a child’s head after birth, “it is supposed to protect against drowning.”

As we’ll see, both meanings have relevance for this film, and we can see many references to both kinds of caul in the film, not least Henry’s ubiquitous semi-transparent raincoat.

The spiderweb is also referenced in the wire that encloses Harry’s work – and especially when his nemesis, Bernie Moran tempts and taunts him through that wire.

Another recurring visual trope in the film is reflections – many times we think that we are seeing the truth, only to discover that it’s a reflection of the truth. Or, near the beginning of the film, that people think they’re seeing reflections of themselves, when they’re actually being spied on and denigrated.

But it’s when we start looking at the themes of the film that we see it’s timeliness, and why it is currently having a revival.

What is truth? Is there such a thing as objective truth? How do your fears distort your ability to discern the truth?

What’s worse – small but tangible ‘sins’ with for which you have clear and direct responsibility, or large but intangible sins, with indirect responsibility?

How far can you take the argument that ‘I’m just doing my job’?

Can you protect yourself from the effects of other people without losing the ability to connect, no matter how hungry you are for connection?

July 2025 - Spirited Away

Tonight I’m going to screen the most widely esteemed animation film ever made – Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 film SPIRITED AWAY. Although it received some recognition at the time – including the 2002 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature – its reputation since then has continued to grow.

Just recently the British Film Institute named it the fourth best film of the 21st century, and the New York Times survey of 500 working writers, directors and actors named it eighth best film of the 21st century.

It’s a film that is full of multiple meanings, extraordinarily beautiful visual design, and wonderfully imaginative narrative and characterisations.

At the surface level, it’s a simple coming of age story about a petulant young girl Chihiro becoming an adult.

But it’s about so much more than that. There are so many levels of meaning to this film that there must be at least 100 things we could talk about afterwards. In fact, you may struggle (as I do) to tie its meanings down. It might look like a typical Hero’s Journey story, but it doesn’t go for neat Western conclusions.

I want to focus on two other things.

The first is something that is often overlooked in filmmaking – the sound.

And not just the wonderful score, which wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar that year (which was won by Elliott Goldenthall’s score for Frida - anybody remember that? Mmm - I thought so.)

I want to talk about the way that the dialogue and sound effects have been put together, and how they affect us – often in a subliminal way so we don’t even notice the magic they’re working on our emotions.

Pixar’s resident genius John Lasseter counts Hayao Miyazaki as one of his greatest influences, so when Studio Ghibli – Miyazaki’s studio, struggled to raise the funding for Spirited Away during the economic downturn in Japan at the turn of the century, he persuaded Disney to invest. Subsequently Disney/Pixar released an English-language version of Spirited Away, which no doubt greatly assisted its acceptance into the American market.

But I’ve chosen to screen the Japanese version because I much prefer its sound mix, even though it forces us to read subtitles.

The Japanese version is much sparser, and much less dense than the American version. There is much more silence – what the Japanese call Ma, the empty centre – in the Japanese version.

And to understand how this happens, I’d like to explain how you get the sound on an animation film.

So buckle in for a quick ride through the process of putting together the sound.

The first part of sound is the dialogue.

In an animation, the dialogue is usually the first thing that is recorded, because when the characters are finally drawn, the movements of their mouth needs to be synchronised with the existing dialogue. And you need the dialogue, as spoken by the actors, like a radio play, to do that.

So, once the production has a locked off script, and some concept sketches, the actors go into a voice recording studio with the director, and record the entire script. Sometimes one by one, just doing their lines, and sometimes in small groups like a radio play.

Very often the actors are shown some concept sketches of the character they’re playing, and the characters they are interacting with, and perhaps even draft versions of some key sequences.

They do the rest from their imagination. And you end up with all the dialogue for the film. But unlike in a real film, that dialogue is very clean.

When you record the sound for a live-action film, you don’t only capture the dialogue, you capture all the sounds that are happening in that space at the same time. Sounds that we tune out in real life like air-conditioning, the buzz of fluorescent lights, distant traffic, wind, et cetera et cetera.

Although we can tune these sounds out in real life, once they’re recorded they become melded with the sounds we really want, and it’s much harder to tune them out. On a live action film you spend a lot of time trying to clean up the dialogue, or hide inappropriate sounds. Or even match the general background noise across cuts.

The other thing you get in a live action film is the sound of the space. Is it a reverberant space, or a dead space? A big space or a little space? Which is great – as long as the aural space matches the visual space.

The dialogue in an animation film has none of these, and if you want them, you have to add them later, when the visuals are finished. Not only the actual sounds, but the effect of the space on the sound.

More work perhaps, but more control.

At this point on the process, all you have is the visuals, and the dialogue. People walk silently, doors open and close silently, trains go past silently.

So where do you get all these sounds from? You get them in two ways.

You either go out into the world and record them (or buy the rights to somebody else’s recording of them); or you create them in a studio through a very weird process called Foley.

So, if you want the sound of a train approaching from the distance, stopping, and leaving again, you have to go out and find a way to record a real train doing that in a space that’s as quiet as possible.

You may end up on a very remote railway station at 3.42 in the morning with your microphone and your recorder, hoping desperately that the 3.45 train is empty, and no one gets off talking, just to get a clean version of that sound.

And so on for all those other specific sounds. Doors. Lifts, Cars. Etc etc.

And then there’s Foley.

Foley is things like the sound of footsteps, of car keys rattling, of dishes being washed and so on. Generally Foley is people doing things that make sound: walking, cleaning their teeth, getting dressed, hitting each other and so on.

Things that have to be synchronised to the action.

Foley is one of the weirdest and funniest things you can watch happen.

Typically a Foley studio has multiple patches of different surfaces: concrete floors, wooden floors, carpeted floors, sand, gravel, grass and so on. A collection of different doors in different walls. Some drawers and cupboards. And amongst all the other accoutrements, the Foley artists have a collection of different shoes. Loafers, thongs, slippers, stilettos, boots etc etc.

Foley artists typically work in pairs – one recording, and one doing. So, to put in the footsteps of a character, one of the Foley artists will choose the right shoes, and the right surface to be walking on, and then record the sound in sync with the action on the screen – matching the movements and even the mood of the character to get the sound of them walking.

And, if the character is getting dressed, they will have a collection of different materials to rub together to match the sound of the clothes moving on the body of the character.

And so on for all the character movements. Running, hitting, cleaning their teeth, doing the washing up and so on.

It’s a long and painstaking process, but it has two advantages. Firstly, you can get very clean sound. The sound is surrounded by silence.

And secondly, if you’re imaginative, you can give the sound character. You can make footsteps squishy. Or bouncy. Sad. Whatever.

And this is what I’d like to draw your attention to in the sound – the way that a stripped back sound mix allows you to give each of the sounds their own character, and then allows you to put that sound into a space that lets you hear that character.

This film does that wonderfully. The sounds have real individuality. And you can hear it. But you probably won’t notice it.

In the great thing about sound (if you’re a filmmaker) is that it slips under the radar. Most people are more visual than aural, and so they mostly notice the visual things, and the aural slip past their conscious mind and affect the subconscious.

One of my favourite sounds in this film is the hopping lantern, after the train ride. Watch out for it!

The second thing I want to touch on are some specifically Japanese things that are probably not clear to us. I hope nobody speaks Japanese – I’m going to mangle some words now.

Japan experienced an extreme economic downturn at the turn of the century, and that permeates this story. The bathhouse at the centre of the failed theme park is symbolic of that downturn, and of the unsuccessful melding of traditional Japanese values with Western capitalism. The bathhouse as a communal place where everybody is naked and all are equal (no nakedness in this film) vs. the theme park as a commercially created exploitative communal space that has failed.

This idea permeates the story.

We see it in Chihiro’s parents’ clothes and the car they drive (it’s a left-hand drive European car in a country that is right-hand drive). We see it in the way that the river God has been polluted and almost killed by the waste associated with capitalism and consumerism. We see it in your Yubaba’s clothes and apartment which, unlike the rest of the bathhouse which is very Japanese, is very Western. We see it in Yubaba’s slavery to her enormous demanding baby.

We see it in the way that No Face has lost his real character, and has simply become a consumer, taking on the characteristics of this world, becoming bolder and bolder and greedier and greedier. And lonelier and lonelier.

We see it in the character of Haku, who is a reference to the Kohaku River, which is a real river that was dammed and filled in so that apartments could be built along its path.

But perhaps most of all, we see it in the transformation of Chihiro’s parents into literal pigs being fattened for slaughter.

A few key Japanese concepts:

The subtitles struggle to capture the nuance of class and status in the speech – Japanese is a very hierarchical language that not only reflects class, but also reflects the relative status of the people in the conversation.

For example, in the beginning Chihiro uses a demanding mode of language – like a chick demanding food from its parents. Then, when she begins to work at the bathhouse, we hear her moving from Kenjogo (humble speech) to sonkeigo (respectful speech) and finally graduating to adult-to-adult speech.

Kami - the Shinto/pantheistic idea that there is a spiritual element to everything that exists in the world, and so everything should be respected and nurtured. By the way, I should emphasise that the Japanese don’t impose our notions of good and evil on spirituality – they see spirits as more like multifaceted characters containing both good and evil.

Engacho & Kitta!. The importance of cleanliness in Japanese society. Of course the bathhouse itself is a symbol of cleanliness – both in the physical sense, and in the ritualistic sense – cleanliness as something that is both individual, but also communal.

This is nicely captured in the Engacho – Kitta exchange between Chihiro and Haku when she stomps on the slug later in the film – it’s a childhood incantation to avoid being polluted when one accidentally steps in something unclean.

Mottainai - this is a very Japanese concept about the sadness of waste – that to waste something is to fail to pay it respect.

On – the idea that maturation is partly about understanding one’s moral obligations to others, and to the world you live in, and an honourable adult works to repay those obligations.

Together, Mottainai and On point to another core theme in Spirited Away, the idea that learning to work and be a productive part of society is an important part of growing up.

Of course we could argue that Japan’s behaviour during the Second World War, and leading up to the Second World War, demonstrated the dark side of some of these concepts, particularly the application of cleanliness to ethnicity, but Miyazaki, understandably, doesn’t go there.

Instead, he focuses on what happens to a society when those deeply ingrained cultural values get unthinkingly replaced with foreign (capitalist, consumerist) cultural values.

What happens when we lose our name (Chihiro meaning ‘a thousand fathoms’) and it’s replaced with a number (Sen – the number ‘a thousand’). When culture is replaced by an economic system.

March 2025 - Never Let Me Go

I want to start with an apology – of sorts. There is a saying in the film business that dramas do well when times are good, and comedies do well when times are tough. When we’re feeling good, we’re happy to wrestle with difficult questions. But when we’re feeling bad, give us comedy!

Tonight I’m going to smash this rule. I’m going to screen Never Let Me Go, a strange, sad, beautiful film built on a strange sad beautiful novel by the wonderful British/Japanese author, Kazuo Ishiguro. I don’t often screen sad films because, after all, it’s a Saturday night, and we all have enough things in our lives to cope with – especially these days.

In October last year, when I chose the film I would screen tonight, I had no idea what the world would look like now. I had some fears, but they were laughably trivial in retrospect.

So, Never Let Me Go, or as it was known in Germany "Alles, was wir geben mussten," which translates to "Everything We Had to Give, " which is for me a better title, is not really a film for these times.

Not only is it sad, but it’s also a strange kind of period science-fiction hybrid. But, just as all period films are really about the here and now, all science fiction films are always really about our world, no matter how different their world appears to be.

Both period films and sci-fi films are using a device called metaphoric distance to look at our world through the prism of another world or another time, so we can see our own world more clearly.

Never Let Me Go is set in a kind of grey alternative past, where the best aspects of traditional English life are revealed to be no more than a mask.

So, why would you want to write this book, and then make this film? What does the author (unmistakeably Ishiguro in this case, not either the director Mark Romanek or the adapter, Alex Garland) want to say to us in the here and now?

I have my theory, which I’ll share at the end of this piece. In the meantime I want to celebrate two aspects of this film.

The first is the extraordinary transcendent performance by Carey Mulligan, in only her second major film role after An Education. To my mind this is one of the great screen performances of its era -- though as ever, all the acting awards went to much more overt performances.

The second is the way that this film manages to, in a very sophisticated way, build a bridge between allegory and metaphor to address a question that was then, and is still now, at the core of English society, while at the same time maintaining a level of mystery.

The world is full of manuals on how to be a successful author, and they generally make this distinction between metaphor and allegory:

a metaphor is a short simple statement saying that two things that seem different are actually alike (even identical); whereas

an allegory is an extended parallel story that creates one-to-one correspondence between characters and events in the world of the story and characters and events in the real world, in order to make a point about the real world.

Metaphors are poetic and open-ended; allegories tend to be schematic and closed. But, contrary to those writing manuals, it’s possible to find a coherent middle ground. If you’re skilful enough.

“Love is blind,” is a metaphor. But love is an emotion, not a sentient being. How can it be blind?

This is how metaphor works. It takes things that we know to be different, and insists that they are also identical, which forces us to build a bridge between them. A metaphor creates a space for us to fill with our experience and imagination.

“All the world’s a stage” is another well-known metaphor, form As You Like It.

But add the next lines, and it begins to slide into allegory.

“And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages.”

Even more so as Jaques’ speech runs through those seven ages. Yes, there is still some room for our imagination. But less and less, as the possible meaning becomes dictated and constrained by Shakespeare, through his mouthpiece Jacques.

Allegories are coherent collections of metaphors. And in becoming coherent, they tend to lose their openness. Their artistic mystery.

Allegories give more power to the author and leave less space for the reader or viewer – unless there’s another level happening which keeps the allegory hidden.

The Poseidon Adventure is an allegory about hyper-capitalism. As is Towering Inferno, with everybody fighting to get on the top floor as the flames lick higher and higher. However, in both cases, the power of the genre – the disaster movie – means the allegory remained buried for most of the audience.

Perhaps that enables them to speak to more people, even while they said less?

George Orwell’s Animal Farm, on the other hand, never really transcended being an allegory about Stalinism in post-revolutionary Russia. The pigs are never anything but the self-appointed party bosses, the dogs anything but the secret police, and the horses anything but the workers. And the events are quite specifically postrevolutionary Russia.

So, even though recent events have made Animal Farm relevant again, it no longer has the power to shock us with its insight. Instead it has become something of a period novelty, ripe for high school English classes.

Allegories as specific as Animal Farm tend to have short lifespans. Somehow, the underlying universal question which would have maintained its relevance – which I take to be something like ‘is it possible to take power on behalf of others without ultimately taking it for yourself?’ – has become overwhelmed by the specific allegorical meaning.

Incidentally, did you know that Orwell wanted to call the French translation Union des républiques socialistes animales, which has the acronym URSA, which is Latin for « Bear », the animal symbol for Russia? That would have made the allegory even more specific.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Some allegorical films have maintained their power long after the events which gave rise to them have passed.

Casablanca is still a great film, even though America is no longer sitting on the sidelines of a world war, dithering about whether it will join in. And High Noon is still a great film, even though America is no longer under the thumb of Joe McCarthy, and the era of the Hollywood blacklist.

Both films were written with specific allegorical counterparts in the here and now of their world. But both films have lived on because they are built on universal questions of principle and morality that transcend the precise conditions that gave rise to them.

Casablanca says that, since real alliances are built on values not affinities, my enemy’s enemy is my friend. It also says that sometimes the true expression of friendship and love is to let that person go. Finally it says that you can’t use your idealism as an excuse to sit on the sidelines.

High Noon asks that last question in a more direct way: ‘Can you fight real evil by sticking to your personal moral values, or do you sometimes have to put them aside temporarily in order to protect greater values?’

Both films transcend the specificity of their allegorical roots by building their story on universal questions that go beyond their allegorical meaning. Both leave room for us to engage with questions that still matter to us.

Alex Garland’s recent Civil War is a clearly allegorical film that never managed to tap into universal questions. It managed to speak to its time (sort of), but I don’t see it outliving its time. It’s core story simply isn’t strong enough.

Which is ironic, because Alex Garland was also the scriptwriter for Never Let Me Go which, to my mind, neatly sidesteps this problem.

Never Let Me Go somehow manages to sit between an allegory and an extended metaphor. It invites you to ascribe meaning, and clearly has meaning in mind, but never ties you down to a single meaning. It maintains openness and metaphoric mystery alongside an underlying thematic coherence.

It’s a self-contained story that makes logical sense within the world of the story. And while we can see echoes of the real world in the world of the film, there don’t seem to be direct one-to-one connections between any particular character, situation or event in the story and a character, situation or event in the real world.

For example, there is nobody in the story who represents Churchill, Attlee or Bevan – even though I see their ghosts wandering the corridors of Hailsham.

There might be no direct one-on-one connection between the characters and the events, but, for me at least, the story very strongly connects with particular historical events and particular historical consequences.

SPOILER ALERT

For me, the underlying meaning of Never Let Me Go comes into focus in the very last scene when Kathy H, having cared for Tommy during his ‘completion’, stands by the side of a road, looking at a field through a barbed wire fence covered with fluttering pieces of plastic and cloth, and imagines Tommy running across the field towards her.

And I am reminded of the hundreds of thousands of Tommies who died on the killing fields of the Somme and the Ardennes, sacrificing their lives to preserve the quality of life of their ‘betters.’

And of how the NHS was supposed to be the recognition and recompense for that sacrifice, but there was still a two-tier medical system, and people still passively accepted their place in the class system.

Perhaps that’s not what Ishiguro was writing about. Perhaps he really was concerned with the undoubted moral questions of cloning.

But I doubt it. I think he wrote two great books about WWII: Remains of the Day about the English class system and the lead up to the war; and Never Let Me Go, about the English class system and the fallout from the war.

And for me, the film of Never Let Me Go is an example of great adaptation, capturing the many layers of a multi-layered novel.

And if you think that’s easy to do…

February 2025 - The Grand Budapest Hotel

[Note, this essay reflects my own views much more directly than my introduction on the night, where I was attempting to generate open-minded discussion.]

Tonight’s movie – Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel – is the first half of a double bill. Tonight The Grand Budapest Hotel and in March I’ll screen Never Let Me Go, from Kazuo Ishiguro’s great novel.

Both films are about the repercussions of World War II, and neither shows the war directly. Otherwise they reflect very different creative and philosophical traditions.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is unmistakably a postmodern film, and as such is unmistakably a Wes Anderson film – questions of authorship being central to postmodernism.

We can see this from the very beginning, with its frame within a frame within another frame construction. Like a gorgeous miniature nested within a series of increasingly elaborate frames.

In the centre, the story itself. Then the author as a young man hearing the story, as told by one of the participants of the story. Next the author as an old man recalling first hearing the story as a young man. Finally, the young woman coming to pay homage at the grave of the author.

And outside all those frames, the implied ultimate frame – the real author, Wes Anderson.

Every frame, every piece of visual design, and every performance, reflects his very distinct aesthetic. If you were at all familiar with the rest of Anderson’s oeuvre, and you caught 30 seconds of this out of the corner of your eye, you would immediately recognise it as a Wes Anderson film.

It has his fingerprints all over it. He came up with the idea, co-wrote the screenplay, oversaw pre-production, carefully managing every aspect of its look, and then directed the performances and the camera framing and movement.

He even spent months working with the two artists who created the two paintings central to its plot, so they exactly reflected how he wanted to use them and what he wanted them to say.

The film is nothing if not self-referential and self-consciously clever. Content follows form, and that’s half the fun of watching.

Anderson’s films never draw on any cinematic or artistic genres or tropes without pointing out that he is aware that he is doing so, is deliberately drawing your attention to their artifice, and assumes that you are in on the joke.

And I am in on the joke. As a pure viewing experience, I love this film.

But at the same time, although superficially pleasurable, postmodernism is often deeply conservative. By focusing on the tangible expression of how things were – the fashion, the design, the music and so on – it uses the nostalgic appeal of those reminders of the past to skate past the realities of that past.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is the story of the loss of something that was once wonderful, told through the eyes of three outsides: a bisexual man, and orphaned Arab gypsy, and a Jew. The condemned of the Holocaust.

There is no doubt that, in his own way, Anderson is attempting to wrestle with the impact of Nazism on Europe.

But postmodernism tends to substitute the underlying meaning of things with the surface appearance of things. All too often postmodernism replaces philosophy and morality with taste.

And because it is, above all else, about taste, it generally chooses to showcase only the most tasteful aspects of the past. Postmodernism is essentially nostalgic, and therefore essentially conservative.

Never Let Me Go is much more classic cinema. Although it is made very skilfully, it’s made within the conventional cinematic language of the well-made film, in which the hand of the creator is hidden behind the work. And it’s essentially a collaborative project.

Can anybody even name the director of Never Let Me Go, or any of his other films?

Rather than content being in service to form, with form drawing attention to the creator, as it is in The Grand Budapest Hotel, in the film of Never Let Me Go form is in service to content, and the creator is subservient to the work.

If Never Let Me Go has an auteur, it’s Kazuo Ishiguro, who wrote the novel and co-wrote the screenplay.

Ishiguro is a Japanese-born writer who has lived in England since he was five. He brings an insider/outsider sensibility to his writing. This is especially visible in the two remarkable novels he wrote set in England and dealing with the impact of World War II on the working class of England, Remains of the Day, and Never Let Me Go.

Both made into excellent films.

Although he has written across several genres, Ishiguro is decidedly NOT a postmodernist, and we can see the differences clearly if we compare the roles of Gustav in The Grand Budapest Hotel (Ralph Fiennes) with that of Stevens in Remains of the Day (Anthony Hopkins).

Both men have their origins in the lower classes, but have climbed as far as they possibly could within a very hierarchical system. Both believe that they have, through their service, escaped the limitations of their birth. They are servants, but they are also masters, within their realm.

In both cases their position is totally dependent on the rigid hierarchy that they have climbed so successfully. Both are heavily invested in facilitating and supporting the status and position of their ‘betters’. Whatever that takes.

Gustav, a former lobby boy himself, has carved a niche in the world of the upper class through flattery, service, impeccable manners, unflappable je ne sais quoi and complete irreplaceability. A niche in which he not only survives, but thrives.

Stevens has also carved a niche for himself in service to the great and mighty. But Stevens’ master is looking for discretion and silence, not unflappable je ne sais quoi. Unlike Gustav, Stevens has been forced to suppress everything he feels, and sacrifice everything he cares for. He is voluntarily bound in chains of servitude that even love cannot break.

While The Remains of the Day, like Never Let Me Go, looks at the damage done by class, under its charming surface The Grand Budapest Hotel reflects a smug ‘rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate’ view of class, where if only people knew their roles and played them, all would be right with the world.

It is essential to Gustav to maintain a romanticised view of the world, because that is the only world in which he can be successful and happy. There are no bread queues in Zubrowka. No starving children. There is a crippled shoe-shine boy, but no veterans of the first world war hobbling around on crutches. The currency does not devalue by half in a morning.

Instead, Gustav insists on living in a redundant world of spa baths, priceless art, and exquisite pastries. Zubrowka is an entirely, and charmingly, fictitious version of Mittel Europe between the wars. As the elderly Zero says of his mentor, ‘To be frank, I think his world had vanished long before he ever entered it – but I will say: he certainly sustained the illusion with a marvellous grace!’

Not only does Gustav sustain the illusion of perfection long after it has vanished, so does Anderson.

But perhaps that’s appropriate. Perhaps it’s even astute.

Frankly, I get endless pleasure from the capers of Gustav, Zero and Agatha. And I’m obviously not alone.

The Grand Budapest Hotel remains Wes Anderson’s most successful film. It was released in March 2014, was nominated for nine Oscars in 2015, including Best Film and Best Director, and won four:

Costume Design

Hair and Make up

Production Design

Music – original score

To my mind it’s also Anderson’s most creatively successful film. I find much of his work ephemerally pleasurable. They’re like a little exquisite desert – a Mendl’s pastry if you will -- that is intensely pleasurable in the moment, but once swallowed, only the memory of the taste remains.

But is that a problem? Does the mix of artifice with a serious subject work for you?

And now for some trivia.

Speaking of artifice, Anderson commissioned both paintings at the centre of the story, so they are both, in a sense, fakes.

Both painters talk about how painstaking the process was of creating a work that exactly fitted Anderson’s requirements. In the case of Boy With Apple, painted by the English portrait artist Michael Taylor, to the extent of finding wormwood riddled wood for the frame.

Boy with Apple is a pastiche of paintings from the Mannerist period of the Renaissance, particularly the work of Bronzino, who was a leading light of the mannerist movement, and the court painter to the Medici’s in the early 16th century.

It’s also, very fittingly, a gender-reversed take on that hoary old excuse for representing female nudity in art: The Temptation of Eve.

The painting that replaces it on the wall is certainly not relying on time-honoured traditions to represent female nudity and sexual pleasure. This painting is a pastiche of the work of pre-war Viennese symbolist painter Gustav Klimt and his much bolder pupil, Egeon Schielle, created by American commercial artist Rich Pellegrino, who makes a living creating heroic portraits of American football and basketball players.

Incidentally, Klimt gets a lot of coverage in the film. Not only is Gustav named after him, the dress that Tilda Swinton – Madame D. – wears when she leaves the hotel for the last time is a copy of the dress in Klimt’s famous painting The Kiss.

And the entire story about Boy with Apple is a reference to the great art theft and destruction that took place once the Nazis gained power.

Both Klimt and Schielle’s work featured prominently in the famous exhibition of Degenerate Art in a tiny basement gallery in Munich in 1937, as the counterpoint to the Hitler-approved Great German art exhibition in the enormous new city gallery next door.

The official ‘this is good art’ exhibition drew half a million visitors. The badly hung higgedly-piggedly ‘this is bad art’ exhibition in the basement next door drew over 2 million.

For film completists among you, this exhibition is referenced in the Henckel von Donnersmarck film Never Look Away, about the painter Gerard Richter.

Finally, you may wonder what was happening in October 1932, so specifically mentioned.

In general, Mussolini was already in power in Italy, and was beginning his wars designed to create an Italian empire in the Balkans, Libya, Ethiopia and the islands of the Mediterranean Sea.

Meanwhile, in Germany, the Chancellor Paul Hindenburg made one last attempt to appoint a government that did not include the National Socialists who, with the Communists, were the biggest parties in the Reichstag. They of course wouldn’t work with each other, and no other party could form government without an alliance with one of them. A stalemate.

Finally resolved in early 1933, when Hitler was handed the reins – reins he was not to relinquish until he had murdered over 6 million Jews and others, destroyed much of Europe, and bitten on the cyanide capsule in his Berlin bunker.

But that’s another story.

December 2024 - Divertimento

Hello everybody, and welcome to the last First Saturday Film Club screening for 2024.

So, thank you. I’m planning to do this again next year, and I hope I’ll see you there. We’ll start on February 1 with Wes Anderson’s film Grand Budapest Hotel which – if you haven’t seen it already – is a deliciously stylish romp.

And, I would argue, Ralph Fiennes’ finest performance – comedic performances are always underrated, even though they are much, much more difficult to achieve than dramatic performances.

Tonight I’m screening a French film only released this year called Divertimento. I don’t want to say too much about it now, because I don’t want to spoil the experience by encouraging you to analyse it as you go.

I’m just going to say something about the beginning and the end of the film, so once the film is underway, you can just let yourself go with the flow.

Like many films, the ending of tonight’s film faces the beginning, especially in the way it uses a particular piece of music.

It’s quite common for the end of the film to face the beginning of the film – by which I mean that the ending is in some ways a new version of the beginning. Constructing your story like that helps give the narrative a sense of coherence and closure. But there’s another reason too.

That’s because when you put the end of a film up against the beginning, it’s a way of unconsciously benchmarking whether change has happened during the story. We can see that there is a connection between the beginning and the end, but is there are also a difference?

Did anything change over the journey of the story?

That’s important because you can divide almost all stories into one of two shapes, and films are no different.

Either the story is about the possibility of change, or about the impossibility of change. Or the futility of change, which is a subset of the impossibility of change.

Most Hollywood films are about how it is possible to change the world, change your relationships, perhaps even change yourself – though always with some effort, and at some cost.

Even when Hollywood does make films about the impossibility of change, they are almost always structured as comedies, and almost always carry a coda in which change is finally achieved.

Films from other cultures – European, Japanese, Chinese et cetera – are much more likely to say that change is impossible – that human nature and human relationships and human society are largely out of our conscious control, and though we might act as if we are able to change things, in truth we are essentially powerless against the forces of time and history.

This is especially true of what is called the modernist movement in film, which came out of the countries that were most deeply affected by the 2 world wars in Europe, and the associated emergence of existentialism in philosophy and literature.

As a social observation, in my experience when Americans tell anecdotes about themselves, they are mostly about their successes, whereas when Australians tell anecdotes about themselves, they mostly about their failures.

Beliefs about whether change is possible or impossible are deeply embedded in culture.

But I’m going to reassure you right now, that I wouldn’t choose a film for the last film of the year that was about the impossibility of change. Divertimento is absolutely about the ability to change yourself and change your world.

The second thing I want to talk about is a new emotion. Or rather, a newly named emotion.

You’ve no doubt heard the claim that the Inuit have 30 different words for snow (or was it 50?) – supposedly because they live in a world of snow, and each kind of snow has a different effect on their chances of survival in a harsh world.

Sadly, I’ve discovered that this is probably an Arctic myth, but similarly (and in this case truthfully) it’s true that different cultures divide a rainbow differently to our culture. Some cultures only divide the rainbow into 6 colours (for them indigo and violet the same colour) and some cultures have only 5 colours (they also merge what we think of as yellow, green and blue into 2 colours).

And now it appears that psychologists and cultural anthropologists in Western society have decided that there is an emotion that needs to be named and separated from the emotions that we are familiar with – that just as green is a mixture of yellow and blue, although this emotion is a mixture of a number of familiar emotions, it deserves its own name.

And that name is kama muta. 2 words, k-a-m-a m-u-t-a. Catchy huh? The person who gave it this name – Alan Fiske - who calls himself a psychological anthropologist, took it from a Sanskrit phrase meaning “to be moved by love.”

And it happens that Kama Muta is an emotion that many films want to trigger in the audience – and I would argue, in the case of the film we going to see tonight, successfully.

So, what is kama muta?

In short, it’s that warm fuzzy feeling you get in your heart that makes you feel at one with the universe, and at one with each other. It’s an intense and brief feeling of communal love.

You might have got it holding your newborn child for the first time. Or seeing an Australian swimmer with one arm and no legs below their knees win a gold medal at the Paralympics. Just the other day, my wife Sophie definitely got it when I told her that the gorgeous 2-year-old who lives across the street saw me and asked, in a disappointed voice, “But where is Auntie Sophie?”

Some national anthems create a sense of kama muta – even if you’re not French, I suspect a massed choir singing The Marseille triggers kama muta in most people.

Perhaps not the Germans. Or the Algerians, for that matter. Because, sadly, kama muta can also be connected to extreme and unhelpful forms of patriotism.

I, for one, are quite happy that Advance Australia Fair fails miserably on that count. As Samuel Johnston said, “Patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.”

If you want your movie to have something to say, it’s not enough to make a rational logical argument. For it to really stick with the audience you need to connect it to an emotion.

And one of the best emotions you can use to do this is kama muta. If you can reinforce the thesis of your film by connecting it to a moment of kama muta, it can be very powerful. Remember those Telstra ads about calling home?

But of course, like many powerful things, it can be used for better or for worse.

So, what about Divertimento? Does it deliver kama muta for you, and does it do it as a force for good?

It certainly does it for me.

November 2024 - Arrival

Tonight I’m going to screen the 2016 science-fiction movie Arrival, which was directed by Denis Villeneuve, and adapted by Eric Heisserer from Ted Chiang’s novella “Story of Your Life.”

Arrival was nominated for 8 Oscars in 2017, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Editing, Best Production Design, and 2 different areas of sound, and it won for Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Sound Editing.

Extraordinarily (for me at least) Amy Adams wasn’t even nominated, though she did get lots of recognition in other awards. (Emma Stone won for La La Land. What do people know, right?)

When I was choosing the films to screen for the second half of 2024, I realised that two years into our film club I still hadn’t screened a science-fiction movie.

The challenge for me is that you are all sophisticated adults, so if I was going to screen a science-fiction film, it needed to be sophisticated and adult – both cinematically and philosophically. No superheroes in ripped T-shirts and body-hugging spacesuits fighting wars in space with evil aliens, space guns, death stars et cetera et cetera, but something that asks an interesting question in an interesting way.

For me, Arrival meets both those criteria – but in doing so I also think that it’s potentially confusing the first time you see it. Certainly I didn’t get what it was really about until I was thinking back on it afterwards, and as a result I got much more from watching it a second time than the first time.

So tonight I’m going to do something I normally avoid – I’m going to tell you a bit about what the film is about upfront, because I think we can short-circuit the path to understanding the film and that way enhance your enjoyment of it.

But first, a little bit about the makers.

Denis Villeneuve is a French-Canadian director who first got international attention with his 2010 film Incendies, which is a slightly mystical film about adult twins journeying back to an unnamed Middle Eastern country to track down a father they thought was dead and a brother they never knew they had in order to deliver a letter from their dead mother to each of them.

Then in 2015 he made Sicario, with Emily Blunt playing an idealistic FBI agent caught up in the tangled loyalties and politics of stopping drug running across the border between the United States and Mexico.

Since then he has moved much more into big budget sci-fi, including Dune 1 and 2 and Blade Runner 2049.

The screenwriter Eric Heisserer started out writing horror films with Wes Craven and has largely written horror adjacent movies since. But along the way, in an attempt to break out of that world, he wrote an adaptation of a story by a hugely talented but at the time largely unknown outside the science-fiction world writer called Ted Chiang as a spec script – that is an uncommissioned script that you shop around in the attempt to get some attention – and eventually it got picked up and made.

This eventually became the film we are seeing tonight.

So, now to the film itself.

I’m sure you’re all familiar with that old artistic aphorism that ‘…good art matches the form to the content.’

I think that one of the problems with understanding Arrival is that, despite the best efforts of a very talented team, it’s almost impossible for the form of Arrival to match the content of Arrival – because the content of the film is almost opposite to the form of cinema, especially in relation to the idea of time.

The film is asking the question ‘What if time is not actually linear in the way we experience it, but could flow equally in either direction?’ Which would mean that past, present and future could all coexist in our mind.

‘And what if some human beings were able to break out of our linear time straitjacket, and perceive time as being like simultaneous layers? They would then have access to every moment, every experience, and every emotion they would ever feel across their life.’

Which all leads to the big question: ‘If you have the ability to know everything that was going to happen to you in your life – good and bad, wonderful and awful – would you still live your life to the full?’

Big questions, right?

Cinema, on the other hand, is as much about withholding information as giving it. Cinema uses information almost as a form of currency, with the filmmaker doling it out bit by bit in order to create maximum drama in their story.

The audience has almost no control of what they see or hear, or of when they see or hear it. The filmmaker controls what’s inside the frame or outside the frame, what’s hidden in the gap between cuts, the order we get the information, and when we get the information. We are almost entirely at the mercy of the filmmaker, as she controls what we know and don’t know, and the rhythm and pace and order in which we glean that knowledge.

We can’t even flick back a couple of pages to clarify something.

So, the film of Arrival is trying to do contradictory things: on one hand it’s asking ‘What if time is reversable and therefore effectively simultaneous?’ but it does it through a medium which uses time in a very linear way.

And although I think it does this very intelligently, it is still potentially confusing. For example, by the end of the film we realise that the first sequence in the film is really the end of the film, and happens after almost everything that we are about to see.

But because of the way that we experience cinema (and for that matter life), the first time we see the film, we tend to perceive that first sequence as the ‘now’ of the film, and the following sequence as the ‘next’ of the story – the ‘and so now…’

And in truth, it seems to me that we are deliberately mislead as part of the filmmaker’s strategy, so we perceive Amy Adams’ aloneness and depression when she gets the call to help with the aliens as the result of what we saw at the beginning, when the connection is actually the reverse of what we read.

But now you know. When you watch the film, remind yourself that almost everything you see after that first sequence is what leads up to that first sequence, not what follows it. And all the little flash sequences are ‘memories’ of something that hasn’t happened yet.

I agonised whether or not to tell you this, but I think its justified because I believe that it will immeasurably enhance your understanding and enjoyment of the film

But all this confusion is not just a filmmaker being too clever for their own good. It’s actually central to what they’re saying. Let me illustrate.

I’m standing here in front of you. Which direction from me is the future, and which the past? The future is in front of me, the past is behind me, right?

That perception is true for many cultures, but it’s not universally true. In some cultures, the past is in front of us, and the future is behind us.

Whereas in our culture we think of the future as the direction in which we going – the direction our 2 eyes point so we can see where we’re going, and the direction our 2 feet point to take us there – for other cultures the past is what we can see and know, and the future is what we can’t see or know.

Therefore, for them, the future is behind us, and the past is in front of us.

And this difference in perception has cultural significance.

Our Western culture is about relentless progress and movement; the other cultures are about living in the present, and about perception.

‘Yesterday’s history, tomorrow’s a mystery, live for today.’

But, to use another time analogy, which is the chicken, and which is the egg? Which came first? In these differences, did the culture precede the perception, or did the perception precede the culture?

As the film also explores, this is also a question about language. The film references something called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which basically says that the language we use doesn’t just reflect our perception of reality, it shapes our perception of reality.

Head hurting yet? I know mine is.

But the aliens in Arrival are not built like us with only two eyes and two feet, both pointing in the same direction. They are heptapods. They have seven legs and seven eyes. For them, there is no front and back, there is just ‘around’ – and as it turns out, for them there is no past and future – there is just multiple layers of the present. For them time is not in front of them or behind them, it’s around them.

Amy Adams is playing an extraordinary linguist, who is able to understand the aliens even though the underlying world view is so different.

But, in doing so, she begins to also take on their perception of reality, which gradually bleeds into her day-to-day life, and eventually permeates it.

Which creates an enormous dilemma for her – if you know what’s going to happen in your life, both the good and the bad, the joyful and the painful, would you still choose to live it? What matters, the journey or the destination?

This question turns out to have enormous implications – perhaps too many to be explored at depth in a film that runs for less than 2 hours.

Is happiness and achievement a zero-sum game, where any gain must be balanced by a loss?

What are the implications for capitalism if gain and loss are the same thing, just played in different directions?

This is referenced very early in the film, in a question about the underlying meaning of the Sanskrit word for war. It’s also implicit in the enormous question that powers the oppositional narrative of the film: ‘but what do the aliens want; can we bargain with them; can we get more than we give; and can we outwit the other nations?’

There is also another enormous question in the film, which is ‘if the language we use reflects and shapes our view of reality, so that we can never be sure that our perception of reality matches anybody else’s – especially if they speak a different language and belong to a different culture – can we ever really understand each other?’

Arrival wrestles with some meaty intellectual questions. But it’s also powerfully emotional in a way that I find deeply satisfying.

Now for a few metaphors to look out for in the film.

The screen through which the humans and the aliens communicate. Remind you of anything? Like what you’ll be looking at shortly? Notice also the contradiction – that like all forms of communication it is both transparent and a barrier.

Many, many references to circularity and versions of circularity and reversibility. Corridors, images, staircases (a double metaphor about climbing and circularity), jewellery, the first and last words that Amy Adams says to her daughter et cetera et cetera

Palindromes – Hannah’s name, and the theme music are both the same, whichever direction you read them or hear them.

References to the heptapods themselves in Amy Adams’ fingers, and her daughter’s costume during the tickling sequence.

The names they give the heptapods – Abbott and Costello – which in this case doesn’t refer to right wing Australian politicians, but to a pair of comedians whose most famous routine ‘Who’s on first?’ is all about miscommunication through understanding language differently.

Note the reference to the canary in the coalmine? Listen out for when those chirps are incorporated into the sound mix, and what they portend.

Lots and lots to talk about. I hope you enjoy the film.

October 2024 - Hell or High Water

I’ve been thinking about screening a Western for some time, because Westerns are such a core part of cinema history. But I wanted to explore how they’ve gone beyond the white hat/black hat, cowboys versus Indians simplicities of the original Westerns, and evolved over time into something much more interesting.

Because Westerns have been around for a very long time – well over a century. Which speaks to both their resilience and their adaptability.

Arguably the first Western was made in 1903 (The Great Train Robbery), and they’ve been a staple of American studio production ever since. Early television was populated by Western serials, which were themselves derived from the supporting feature tradition in cinema. Because, in the days that the main feature wasn’t preceded by ads for fast food, cars and telephone companies but by a cartoon and a B-movie, the B-movie was very often a Western.

But over the decades many Westerns have made it out of the supporting feature category onto the main stage. Ever since the Oscars were established, a Western has been nominated for Best Picture on average every three or four years.

Just to remind you, here is a short list of seminal Westerns: Stagecoach; Red River; High Noon; Shane; The Searchers; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; The Wild Bunch; Dances with Wolves; Unforgiven; Paris, Texas (which is a kind of sequel to The Searchers half a century later); and so on.

I’m sure you can add a few of your own. The Western has proved to be a strikingly resilient and adaptable genre - because it taps into a core American mythology.

Tonight I want to screen what is usually called a neo-Western, released in 2016, and itself the recipient of four Oscar nominations – Best film, Best Original Script, Best Editing, and Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Jeff Bridges (though I have to warn you, his nomination was certainly not for clarity in speaking).

This is a terrific film – but hardly anybody saw it. It had a low budget – only $12 million – and it made about $35 million back – but that wasn’t enough to save the production company, which went bust.

But before we watch it, let’s explore some of the ways that Westerns have evolved over the years. And we can’t really look at how Westerns have evolved without understanding the concept of Manifest Destiny.

The concept of Manifest Destiny was coined in 1845 by John L O’Sullivan, a newspaper editor and political agitator, as the core of his argument that the United States should annex Texas, which had declared independence from Mexico in 1836 as a result of Mexico abolishing slavery in 1829. The southern slaveholding states of the United States were very keen to bolster their numbers to prevent the encroachment of the federal government on their state rights – i.e. the continuing legality of slavery, which was often presented as a state’s rights issue.

Manifest Destiny essentially wrapped a pro-slavery State’s Rights argument in ethnic nationalism, arguing that it was the manifest destiny of white people to expand across the entire North American continent from coast-to-coast, pushing out Mexicans and any inconvenient original inhabitants along the way. Its enthusiastic adoption as both an argument and a rallying cry led to decades of violence and dispossession – all glorified in the original Westerns.

Manifest Destiny is a seminal part of American Mythology, and for many years Westerns were the most visible cultural manifestation of that doctrine. Even now, nearly two centuries after it was first propounded, and long after end of the original conditions that lead to articulation, its underlying values continue to taint American politics.

Manifest Destiny was underpinned by several key beliefs:

Racial Superiority: the belief that Anglo-Saxon Americans – particularly Protestant Christians – were morally and intellectually superior to all other races.

Divine Providence: in His wisdom, God brought white people to North America, had granted them Dominion over all the land, and expected and demanded that they take over the land, spreading democracy, Christianity and civilisation in their path.

American Exceptionalism: because America was chosen by God as the home for his people and was therefore morally and politically superior to all other nations, American politics was not to be challenged or questioned by political or social ideas that arose in other countries – such as the abolition of slavery (or, in more recent times, universal healthcare).

Sound familiar? I told you it was an enduring myth. But, as expressed in Westerns, it has also been an adaptable myth, capable of being turned on its head by different generations of film makers.

For decades those early cowboys and Indians Westerns painted a simplistic picture of the cowboys as heroes and the Native Americans as villains. Those powerfully simple stories preserved the mythology and values of Manifest Destiny long after the massacres and the dispossession that it underpinned had successfully ended.

But genres survive by being adaptable, and Westerns have proved to be remarkably adaptable. The Western tradition still has potency because the original myth is still a core part of American identity – but the meaning of the Western has changed as American culture has changed.

John Ford used the Western to turn examine the tension within the white frontier settler communities between those seeking the peace and community, and the violence that created those communities and maintained the peace within them – asking whether there was a place in civilisation for the men who carved out a place for civilisation.

Two of his greatest films, The Searchers and Stagecoach, bring different approaches to this same question.

Unfortunately, in putting his focus on the tensions within the white settlers, Ford’s films also bring with them a stereotypical view of Native Americans – which Ford himself acknowledged later in his career. After all Ford, who was and remained Irish to his core, had his own powerful national traditions of violent suppression and dispossession to draw upon.

And then, in 1952, at the height of McCarthyism, High Noon celebrates a commitment to individual conscience and clear-eyed morality that challenged the witch-hunt that was the House Un-American Activities Committee’s pursuit of its imaginary enemies within the nation – and was recognised by that Committee as doing so.

Those Hollywood liberals and communists!

Then, in 1962, John Ford made The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, questioning the entire mythology of Westerns, and shows how truth has been sacrificed in creation of those myths.

The Wild Bunch (a remake of Kurosawa’s Japanese masterpiece, Seven Samurai) and Soldier Blue were both made at the time of the Vietnam war – and it’s easy to see how they reflected America’s changing view of the nature and heroism of war. Of course, right about the same time John Wayne was making Green Berets, an old-fashioned Western with the Vietnamese as the Indians/Mexicans, and the Green Berets as the Texas Rangers.

And then came a series of films reversing and revising the power relationship between the white intruders and the native inhabitants, like Dances with Wolves. And others, like Django Unchained (and, if we go back a long way, Blazing Saddles), which explored the role of African-Americans in that world.

Recently there has even been a television series that reverses the roles of men and women in the West – Godless – and if you haven’t seen it, I highly recommend it.

I could easily extend this exploration of the various ways that Westerns have reflected and challenged the changing American social and political values, but I’ll save you from the screen studies lecture, and move on to tonight’s film.

Hell or High Water is the middle film of the trilogy of what are generally called neo-Westerns written by Taylor Sheridan, who started out as an actor, and then moved on to being a writer/producer. These days he is probably best known as the creator of the TV series Yellowstone, and its various spin-offs.

By the way, the other two films in that trilogy are Sicario and Wind River, and they are both worth watching.

The director, David McKenzie, also started his professional life in cinema as an actor – but in Scotland. He’s made many interesting films in Scotland and Europe – but I’ve got a Tim Tam for anybody who can name any of them.

Incidentally, both writer and director continue their acting career with small on-screen moments in this film.

A couple of things to look out for, for our discussion later.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this film came out in the year the Donald Trump was first elected President – many of the things that the film is about plug into the zeitgeist of that time. Just as many of the underlying values of Manifest Destiny are writ large in the MAGA movement.

I also don’t think it’s a coincidence that Jeff Bridges’ partner in the story is played by Native American/Mexican – one of only two non-white roles in the whole film.

What’s going on underneath the surface in this relationship? What is Bridges’ character up to with his constant needling of his partner? Does their first scene together and their last scene together shift our interpretation of that?

Finally, remember how I said that John Ford’s films wrestled with the core contradiction in westerns between community and civilisation on one hand, and violence on the other?

Hell or High Water uses a common narrative trope called duality to explore the same contradiction by embodying it in the two sets of brothers – one literal, and the other metaphorical.

Duality in character development works by taking what could be a single complex and contradictory character and splitting him or her into two characters that each take on one half of the internal contradiction. If one is shy and timid, the other is brash and extroverted. If one is moral and considerate, the other is immoral and inconsiderate.

On one hand they are almost the same person (quite often they are twins) and are bound together in the narrative by a common situation and a common purpose; but at the same time, they are diametrically opposed in character, impulse and action, and bring opposing solutions to the problem. Sometimes for the best – much more often for the worst.

Duality is a very useful device that goes well beyond character. For example, take the last two lines the brothers say to each other – you can’t get a much clearer example of duality than that exchange.

This trope is very common in genres that are essentially melodramatic, because it enables you to externalise internal conflicts and make them more visible, and much more active. Which also allows the film to make its philosophical premise tangible and active – as we’ll see in this film.

As a genre, Westerns are about as melodramatic as you can get. But leave your prejudices about melodrama at the door, because this film is filled with perfectly cast actors bringing strong truthful performances to what could easily be melodramatic clichés. If there was an Oscar for the film with most excellent one-scene characters and performances, this film would be right up there.

So – let’s go to rural Texas, Hell or High Water!

September 2024 - Eat Drink Man Woman

There are some films that are more than the sum of their parts. They might have clumsy dialogue, or performances that don’t quite work, or perhaps longueurs in the storytelling – but when the closing credits roll, you are deeply satisfied.

For me Ang Lee’s 1994 film ‘Eat Drink Man Woman’ falls squarely into that category.

The dialogue we are reading on-screen was originally written in English by James Shamus, a New York screenwriter and teacher, then translated into Taiwanese by Hui-Ling Wang, who wrote the original story with Ang Lee, and then translated back into English by whoever wrote the subtitles. It’s a miracle it’s comprehensible.

The film itself was made very early in Ang Lee’s career, when he was somewhere between being a Taiwanese director and English-language director. Similarly, the performances fall somewhere between Western naturalism Ang Lee learnt at the University of Illinois, and Taiwanese melodramas he grew up with. As does the entire structure and tone of the picture.

And yet, it still works. In a way those contradictions in tone and style speak to the theme of the film, which is about the tensions between those two worlds.

Anyway, I’m a sucker for films about different cultures, and about how, under the skin, human beings share so many similar hopes and fears and ways of looking at the world. Somehow or other, the different world gives me just enough distance and perspective to notice and care about our common humanity.

Especially in the hands of Ang Lee, who despite having perhaps the widest repertoire of any current working director – this is a director who averages a new feature film every 18 months, and his first three films were set in Taiwan; then a period piece set in England (Sense and Sensibility); then The Ice Storm set in 1970s wife swapping suburbia in Connecticut; followed by a movie set in the American Civil War (Ride with the Devil); and then a Chinese martial arts movie (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). And so on. Brokeback Mountain. Lust, Caution. Life of Pi.

But no matter the genre, when Ang Lee manages to tap into the humanity of his characters – as he usually does – there’s something for me to connect to.

Ang Lee was born 1954 into a family of mainland Chinese refugees in a small provincial town in an agricultural county of southern Taiwan. Both his parents were teachers, and they gradually moved to larger and larger provincial towns and higher and higher positions within the school hierarchy. So, like so many artists, he had a peripatetic childhood.

By the time he finished high school, his parents were principals of two adjoining high schools in a much larger town in much more sophisticated northern Taiwan.

And, like many high achieving migrants, his parents wanted and expected him to have high educational achievements. A Professor, at a minimum.

But he failed the university entrance exams twice, and in despair they sent him to the national art school. After he graduated there he spent four years doing military service in the Navy, and then went to America to pursue his dream of becoming an actor.

But he’d come to English late, and never really mastered it. Even now, after a 30-year career directing English-language movies, he still struggles with nuance, and often uses non-verbal psychological games to help the actors find the performances.

In fact, Emma Thompson, who both wrote and starred in Ang Lee’s first English-language film, Sense and Sensibility, spoke about the difficulty he had communicating with his English cast, and particularly the difficulty he had with them questioning his artistic choices. In a Confucian system, you don’t question those above you in the hierarchy.

But it’s noticeable that, despite criticising Ang Lee, she did it with great affection – clearly his underlying humanity communicated with them, just as it does with us. And he clearly listened and adapted.

So, having decided that his difficulty with English probably meant that a career as an actor was off the books, he married his university sweetheart, who was also a student from Taiwan pursuing a PhD in molecular biology, and moved to New York to study directing in the famous Tisch School at NYU. Spike Lee was the dux of the year before him, and he was the dux of his year.

Which got him representation with the William Morris Agency – the biggest agency in New York at the time. But for six years he had no work, and the family – by now four people, with two babies – were completely dependent on his wife’s income.

During that time he wrote constantly, and when the government information agency in Taiwan announced a competition for film scripts set in Taiwan, he submitted two scripts. Those scripts won first and second place, and got him noticed by a Taiwanese film studio, and then got made by that studio.

Those two films – Pushing Hands and The Wedding Banquet – both set in the Taiwanese diaspora in America – became big hits in Taiwan, and critical hits outside it. The Wedding Banquet won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International film Festival and was nominated as Best Foreign Language film in both the Golden Globes and the Oscars.

The third film in what became known as the Father Knows Best trilogy was Eat Drink Man Woman, and is the only Ang Lee film set and shot entirely in Taiwan.